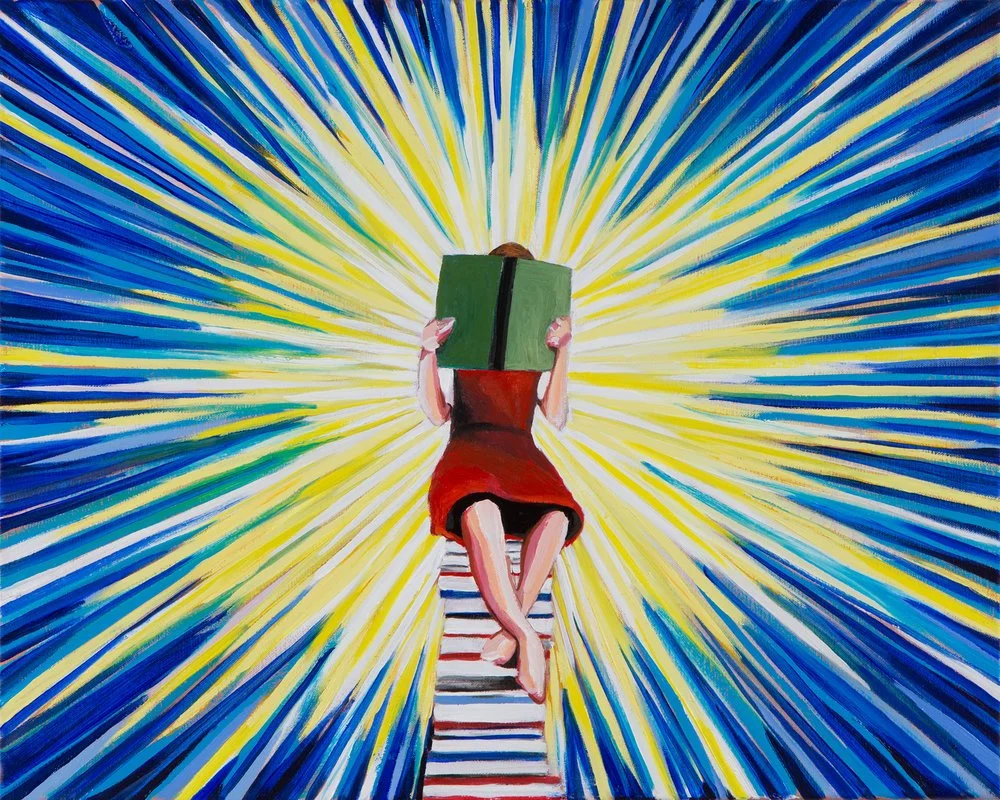

Annika Connor, Because of You

[Creative Nonfiction | Issue 10]

Angela Townsend

On track

When you are a simpleton, you are afforded certain privileges denied to the wise. You are

handed a pouch of giggles every time you see the town name “Ho-Ho-Kus.” You receive a

special dispensation to use toothbrushes emblazoned “Princess” after age twelve. You are fitted

for lenses that see beauty in Secaucus.

I blame my green eyes for the day I missed my train. I knew what time it was. I knew NJ Transit

waits for no one. I knew if I dallied, I would be stranded in north Jersey’s least respected town

for hours.

I just never knew the Secaucus train station had mirth and murals for those with eyes to see. I

couldn’t lower my head to ignore the veteran selling “Buddy poppies.”

It was Memorial Day, and I was coming home from seminary. I’d taken this ride dozens of

times, a wiggly green line from Princeton up through Paterson and on to Port Jervis, where my

smiling stepfather would welcome the holy fool home. We’d rendezvous with Mom for Chinese

food, and I would tell them what I was learning about Hezekiah or the hypostatic union, and

everyone would agree that I should think about learning to drive.

Today, I was learning about Secaucus.

How had I never noticed the tile murals, shiny as seashells? How could I miss the opportunity to

make my grandmother grin from heaven? She’d always stopped for veterans with their red

flowers, tucking them into her car visor until it resembled Flanders Field.

I stopped. Many sparrows had landed around the soldier’s eyes, but I saw the young captain

between the crinkles. I gave him twenty dollars. He attempted to give me twenty poppies.

“No, no, just one is enough.”

“Take two.”

“I’ll treasure them. You know, my Grandpa was in World War II.”

“Where was he stationed?”

“Panama.”

The captain cocked his head. “Panama!”

I forgot Secaucus. I forget my own name when I have the chance to talk about my grandfather.

“Just in case there was an invasion across the canal. He was Air Traffic Control. He doesn’t let

anyone call him a hero, but I disobey his wishes.”

“He’s still with us?”

“He is, and he’s my best friend.”

The captain grinned. “God bless your Grandpa, and God bless you.”

We saluted each other. I spotted the clock among the seashells. I slumped into my simpleton fate.

I was going to miss my train.

I shuffled my Rainbow Brite duffle bag from shoulder to shoulder, studying timetables. If I stuck

to my usual route, I would be in Secaucus long enough to establish residency. I attempted to call

my school-psychologist mother, who should be ending her workday.

“I’m afraid she’s dealing with an emergency.” She hesitated. “A child is in a...bad way.”

I contemplated pulling my own siren. But simpletons assume they will find a way.

I prayed, but the line was busy. I squinted at cab fares on my phone. That would decimate my

Diet Coke budget for the rest of the year. I contemplated returning to Princeton, but I wanted

Chinese food with my parents.

I moped over the map. I spotted something even more beautiful than Secaucus.

Suffern, New York.

Suffern is a freckle on the cheek of congested Paramus. Suffern is a pot of geraniums outside the

mall. Suffern is the warm banana bread at the end of all the road work.

Suffern is where my grandfather picked up the phone every Sunday at 7:30 pm, for his simpleton

princess granddaughter.

I picked up the phone. He answered in his usual style, all octogenarian rage. “HELLO!”

It still made me jump. It was intended to scare off telemarketers and other unsavory characters. It

was part of the music of my life.

I knew what I was about to do to his anxious heart. “Grandpa, it’s Angie.”

I heard the intake of air, lungs filling as his mind filled with horror stills. The air traffic controller

had become a police captain. The captain had become a grandfather, and the grandfather had

become a best friend. The most responsible man in the Northeast Corridor could picture worst-

case scenarios faster than a bullet train.

“Angie! What’s wrong!”

I knew what I was doing to him, and I tumbled over my reassurance. “Grandpa, I’m OK, I’m

just...I missed my train.”

“Where are you? Is there anyone around? Don’t look anyone in the eyes! What town are you in?

I’m coming!”

“I’m in Secaucus.”

“I’m coming!”

“No, no, I can come to Suffern—”

“I’m coming!”

I pictured him tearing through his condo, knocking over all the ceramic angels I’d given him,

pulling on his U.S.S. Ronald Reagan hat and his leather bomber jacket. I saw him racing to the

front door with its owl magnets holding up the immortal grocery list: “Bounty, Stouffers Fish n’

Chips, Total, bananas.”

It took several minutes to convince him of my plan. I would take a different route, he would pick

me up, and when my mother finished saving the world, she would rendezvous with us. “I can be

in Suffern in thirty minutes.”

“I’ll be waiting for you.”

I always enjoyed my train ride, from the flirty trees of Hightstown to the electricity of Elizabeth.

My parents and grandfather worried about the latter, but simpletons are permitted to break smiles

and break bread. Once a man slumped across from me with headphones blaring, they see me

ridin’, they be hatin’... and something inside me insisted I yell, “I love that song!”

The man laughed out loud, and I laughed out loud, and soon a seminarian known as Princess and

a man in red headphones were singing to Car 3 about “ridin’ dirty.”

But the ride from Secaucus to Suffern on Memorial Day was the most beautiful trip in the history

of track. Ho-Ho-Kus laughed in lilacs, and Allendale assembled every spring since Eden. New

Jersey and New York shook hands as the rails rattled beneath me.

At the end of the line, bold as joy, was a silver Ford Taurus. My grandfather rose like a hymn,

captured by the biggest smile I’d seen in ten years.

“Princess!”

“Grandpa!” I fell into his arms. I realized I had been quite afraid. I remembered that simpletons

are sometimes spared their own fear until things get less complicated.

I repeated one of my favorite sentences. “You’re my hero.”

“Today, I accept that!” Grandpa was one inch shorter than me under normal circumstances, five-

nine folded into five-six. But today he regained his full height. He looked like Daddy Warbucks

in Annie, the movie that caused me to weep uncontrollably until I could get him on the phone as

a child. That had not been so long ago.

I tucked a red poppy behind his ear. “Thank you for your service, Grandpa.”

It was six minutes to his condo, where we played backgammon in his mustard-yellow kitchen.

He had changed nothing in ten years, living in a shrine to his bride. Outside the presence of his

princess, Grandpa was grief with claws, resenting everything from my mother’s meatballs to the

existence of Christmas. He would not cross the canal back to simpler times. For reasons no

wisdom could explain, I was the only one with a ferry ticket.

We talked about seminary, and I told Grandpa he reminded me of King Hezekiah, one of the best

people no one has ever heard of. Grandpa pulled out the latest TV Guide to show me the cover, a

picture of Clint Eastwood appearing especially Eastwooden.

“What do you think of his face?”

I had to answer carefully. I knew Grandpa loved Clint like family. In his meticulously organized

cabinet of VHS tapes, organized by year and accompanied by a hand-written book assigning

each a star rating, Clint’s movies had their own section.

“I think he looks full of honor and integrity.” I was talking about my grandfather, not Mr.

Eastwood.

“Look again.”

I looked. I looked at Grandpa. He smiled.

“Angie, doesn’t he have kind eyes?”

I looked. It was true.

“Grandpa, I never would have seen that if you didn’t point it out.” I would never not see it now. I

had always found Clint Eastwood vaguely scary, but my heart surged with affection. “There are

things you can only see when you love someone, I guess.”

He giggled, a sound for my ears only. “You know I love ol’ Clint.”

I knew as much as simpletons are given.

All the planes and trains had landed safely. We played more backgammon and toasted each other

with flat Diet Dr. Pepper. My mother arrived once her student was safe enough. My stepfather

ordered Chinese food. I kissed my grandfather’s downy bald head, and we left him to his nightly

routine of M*A*S*H* and All in the Family reruns. I contemplated missing my connection more

often.

__________

About the author

Angela Townsend is the Development Director at Tabby’s Place: a Cat Sanctuary. She graduated from Princeton Seminary and Vassar College. Her work appears or is forthcoming in Arts & Letters, Chautauqua, CutBank, Lake Effect, Paris Lit Up, The Penn Review, Pleiades, The Razor, and Terrain.org, among others. Angie has lived with Type 1 diabetes for 33 years, laughs with her poet mother every morning, and loves life affectionately. Find her on Twitter @TheWakingTulip and on Insta @fullyalivebythegrace